Share on

Amblyopia, also commonly known as “lazy eye”, refers to a reduction in vision. Unlike other visual disabilities, amblyopia is not directly linked to a problem with the brain’s structure. In other words, there is nothing wrong with any single brain part. The cause is often due to abnormal visual stimulation during early childhood which impairs the brain’s ability to process visual information.

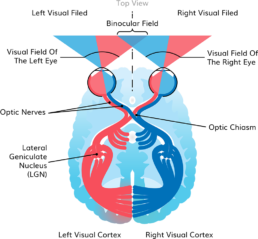

As children, our vision develops by a process of seeing and learning. Our eyes see the face of a parent and the information travels through our two optic nerves, one coming through each eye. Once it passes the optic nerves, the picture arrives at the optic chiasm where it gets mixed in a way it can then go to both sides of the brain.

With this process repeated, our brain learns to interpret the image of a parent as something meaningful, “mum!”. This means that in order for us to be able to see well we don’t only need to have healthy eyes, but also healthy brains and connections in between. This all usually depends on a critical period during early childhood.

The process of developing healthy vision is mostly complete by about 9 years of age. The years before are critical for visual development because if the eye does not provide sufficient visual stimulation to the brain, it cannot mature correctly. The lack of visual stimulation might even result in physical changes that we can see in the brain.

In a study done on monkeys, scientists blocked vision from one eye during early childhood to see if this had any effects on the brain. Lateral Geniculate Nucleus (LGN) is one of the brain’s visual processing centers that is responsible for receiving information from both eyes and interpreting it.

The study found that in monkeys that could only see from one eye, the LGN had very weak connections and did not develop correctly. This is an important study because it shows that amblyopia in early childhood can cause lasting changes inside the brain that can follow all the way into adulthood. There are three types of amblyopia and the treatment will depend on the individual diagnosis. These are Strabismus, Visual Deprivation and Refractive Amblyopia.

Types of Amblyopia

Strabismus is a condition where the eyes are not straight, leading to double vision in adulthood. In children however, the brain is still adaptive and in an effort to avoid the double vision it suppressed the images from the “bad eye”. This prevents double vision but at the same time, it increases the risk of developing long term amblyopia – it will be called “Strabismic Amblyopia”.

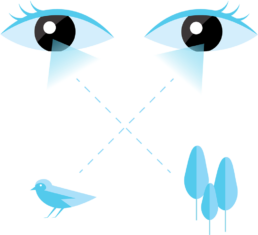

If we look at a healthy person, the eyes are always directed at a single visual object. In the picture below however, someone with Esotropic Strabismus (the eyes cross over), each eye is directed at a different visual object. A child in order to avoid this double vision will suppress all visual information coming from one eye and as a result risk developing amblyopia because of not getting visual input from both eyes.

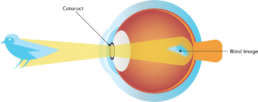

Visual Deprivation Amblyopia has to do with a problem inside the eye such as a clouded lens caused by Cataracts or Corneal Opacities leading to a cloudy cornea. Both conditions might prevent light from entering and passing to the brain. Visual Deprivation Amblyopia might also occur because of eyelid ptosis, a condition in which the upper eyelid droops, preventing correct visual processing.

Refractive Amblyopia is caused by a refractive error (a focusing problem) with the eye. Although the eye is able to receive information from the environment and send them to the brain, the images are out of focus.

This is split into three different types, myopia (nearsightedness) hyperopia (farsightedness) and astigmatism, when the eye is not perfectly round causing distortions. Refractive Amblyopia can affect one or both eyes (uni or bilateral).

Unilateral Amblyopia is also called Anisometric Amblyopia

and that’s when there is a big difference in error between the eyes so the brain chooses to ignore the eye with the higher error.

Refractive amblyopia is usually less severe than strabismic amblyopia and is commonly missed by primary care physicians because of its less dramatic appearance and lack of obvious physical manifestation.

References:

Facts About Amblyopia”. National Eye Institute. September 2013. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016

Webber AL, Wood J (November 2005). “Amblyopia: prevalence, natural history, functional effects and treatment”(PDF). Clinical & Experimental Optometry. 88 (6): 365–75.

doi:10.1111/j.1444-0938.2005.tb05102.x.

Polat U, Ma-Naim T, Belkin M, Sagi D (April 2004). “Improving vision in adult amblyopia by perceptual learning”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (17): 6692–7.

Mohammadpour, M; Shaabani, A; Sahraian, A; Momenaei, B; Tayebi, F; Bayat, R; Mirshahi, R (June 2019). “Updates on managements of pediatric cataract”. Journal of Current Ophthalmology. 31 (2): 118–126.

Cooper J, Cooper R. “All About Strabismus”. Optometrists Network. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, et al. (September 2017). “Vision Screening in Children Aged 6 Months to 5 Years: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement”. JAMA. 318 (9): 836–844.

Elflein HM, Fresenius S, Lamparter J, Pitz S, Pfeiffer N, Binder H, Wild P, Mirshahi A (May 2015). “The prevalence of amblyopia in Germany: data from the prospective, population-based Gutenberg Health Study”. Deutsches Arzteblatt International. 112 (19): 338–44.