Share on

Even though you don’t think about it often, you live in a 3-dimensional world. You are able to avoid bumping into your furniture only because you can tell how far the couch is from where you’re standing. You are also able to drive without crashing into other cars ahead of you, pick up the salt from the table in one go and go down the stairs without tripping at each step. Imagine miscalculating every step on a flight of stairs every time, thinking it was lower or higher. In a world without depth perception, this would happen all the time.

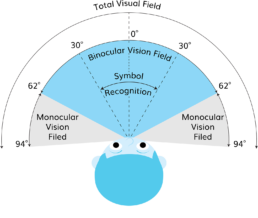

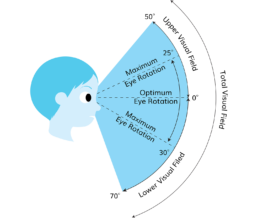

Depth Perception is simply your ability to see the world in three dimensions (3D) and to accurately judge the distance between your feet and each flight of stairs. Each eye is only able to capture a 2-dimensional image and when joined the brain can form a single 3D image.

There are clues in the environment that help us decide the depth and that we can see with one eye (monocular) and some clues that we need both eyes for (binocular). To have depth perception, you must have a binocular vision, commonly known as stereopsis.

People relying on the vision from only one eye generally have less exact depth perception and have to rely on other visual cues to interpret depth.

Monocular Cues

There are several visual monocular cues that can help interpret depth without needing to use both eyes,, namelyMotion Parallax, Interposition, and Aerial Perspective.

If you sit in a moving train and look outside the window, you might notice that the objects closer to you seem to move faster than things in the distance. This is an example of motion parallax and you would be able to judge the distance between objects even with one eye closed.

Now imagine searching for your cat and seeing its tale behind a cupboard. Since the cupboard obscures the cat, your brain would derive that the cupboard must be closer to you. This is also known as interposition or overlapping.

To understand the Aerial Perspective cue, picture looking at a landscape painting. The mountains in the front and clear, sharp and detailed while those in the background have less distinct outlines and are softer or blurred. What creates this effect is the atmosphere between the viewer and the distant mountains, allowing for a monocular depth understanding.

Amblyopia and depth perception

One of the main causes of impaired depth perception and stereoscopic (3D) vision include amblyopia, also known as lazy eye. In amblyopia one eye is weaker than the other because of abnormal vision development in childhood. The two eyes fail to work together leading to binocular vision impairment.

This can have an effect in a child’s life all up to adulthood in many ways including the ability to learn, drive and get employed in areas requiring good depth perception. The earlier the problem is diagnosed and addressed, the more successful the therapy is likely to be.

Poor depth perception affect in your driving: Parallel parking (and parking in general), spacing on the highway, stopping at an intersection (or a stop sign).

Diagnosis starts by visiting an optometrist or ophthalmologist who can do an eye examination. During the test, an optometrist might measure vision in both eyes to decide whether vision in one eye is more blurry than the other. They might also measure how well the eyes work together to decide whether there is any presence of strabismus such as esotropia (the eyes turn towards each other) or exotropia (the eyes turn away from each other).

If the eyes are not aligned correctly, it’s common for the brain to suppress visual input from one eye in order to avoid double vision and as a result, only accept input from one eye. This can lead to poor depth perception and therefore treating visual disorders like strabismus is key to restoring depth perception. Based on the diagnosis, the doctor will be able to recommend the most appropriate therapy.

References:

Tyler CW (2004). Tasman W, Jaeger EA (eds.). Binocular Vision In, Duane’s Foundations of Clinical Ophthalmology. 2. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co.

Birch EE (March 2013). “Amblyopia and binocular vision”. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 33: 67–84

Hess RF, Thompson B, Baker DH (March 2014). “Binocular vision in amblyopia: structure, suppression and plasticity”(PDF). Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics. 34 (2): 146–62.

Birch EE (March 2013). “Amblyopia and binocular vision”. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research (Review). 33: 67–84.

Spiegel DP, Li J, Hess RF, Byblow WD, Deng D, Yu M, Thompson B (October 2013). “Transcranial direct current stimulation enhances recovery of stereopsis in adults with amblyopia”. Neurotherapeutics. 10 (4): 831–9.

Berela, J. et al. (2011) Use of monocular and binocular visual cues for postural control in children. Journal of Vision. 11(12):10, 1-8

Miles, W. R. (1930). “Ocular dominance in human adults”. Journal of General Psychology. 3 (3): 412–430.

Heinen, T., & Vinken, P. M. (2011). Monocular and binocular vision in the performance of a complex skill. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine 10(3), 520-527. Retrieved from: http://www.jssm.org/